In this month's edition of the newsletter, we'll provide a snapshot (no pun intended) of photography mogul Terry Etherton's life. Keep reading for more of his story or click on the "What's New" link below for the latest and greatest updates from Tucson.

As Terry Etherton recounts attending a party at Ansel Adams’ Carmel home, only to have the legendary photographer settle in next to him on the couch and spill a gin and tonic on Etherton’s pants, it’s hard not to be in awe of the life he has lived.

“Did you forego washing the pants?” I ask him, half-jokingly. “I suppose his DNA was on my pants,” he says, laughing. “You know, people often ask me about Ansel Adams. I tell them, ‘I don’t care who you are in this business, everyone in this industry owes him a debt because Ansel was the guy who put photography out there as a collectible and a fine art ... He created the photo market as we know it.’”

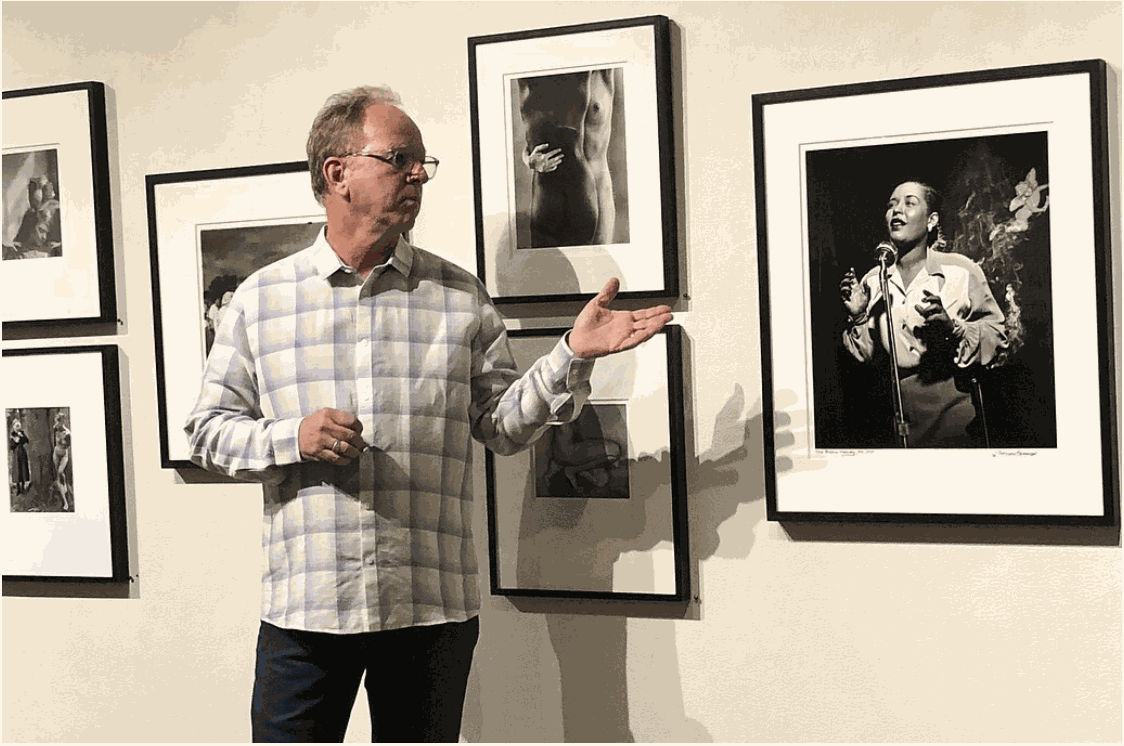

Today, the 73-year-old Etherton is a legend in his own right. He’s the longtime owner of Etherton Gallery, a world-renowned photography gallery that in 2021 relocated to Tucson’s historic Barrio Viejo neighborhood. Etherton anchors the street’s five galleries, all of which set up shop in the soon-to-be National Historic Landmark neighborhood over the past few years.

“You should see this street during an opening,” Etherton said. “It really goes off. It’s unbelievable how busy it gets.”

While Etherton’s recent years have been among the most successful of his career, his early days were touch-and-go, he admits.

Etherton’s eye for identifying worthwhile contemporary photographs dates back to 1981, when the one-time photographer and videographer moved from San Francisco to Tucson and opened Etherton Gallery in its first home, a tiny space where the “rent was cheap” and the swamp cooler worked well. Etherton admits he had no business plan and no experience, but he was equipped with several intangible skills. Chief among them: his ability to identify photographs that tell thought provoking and often uncomfortable or even controversial stories.

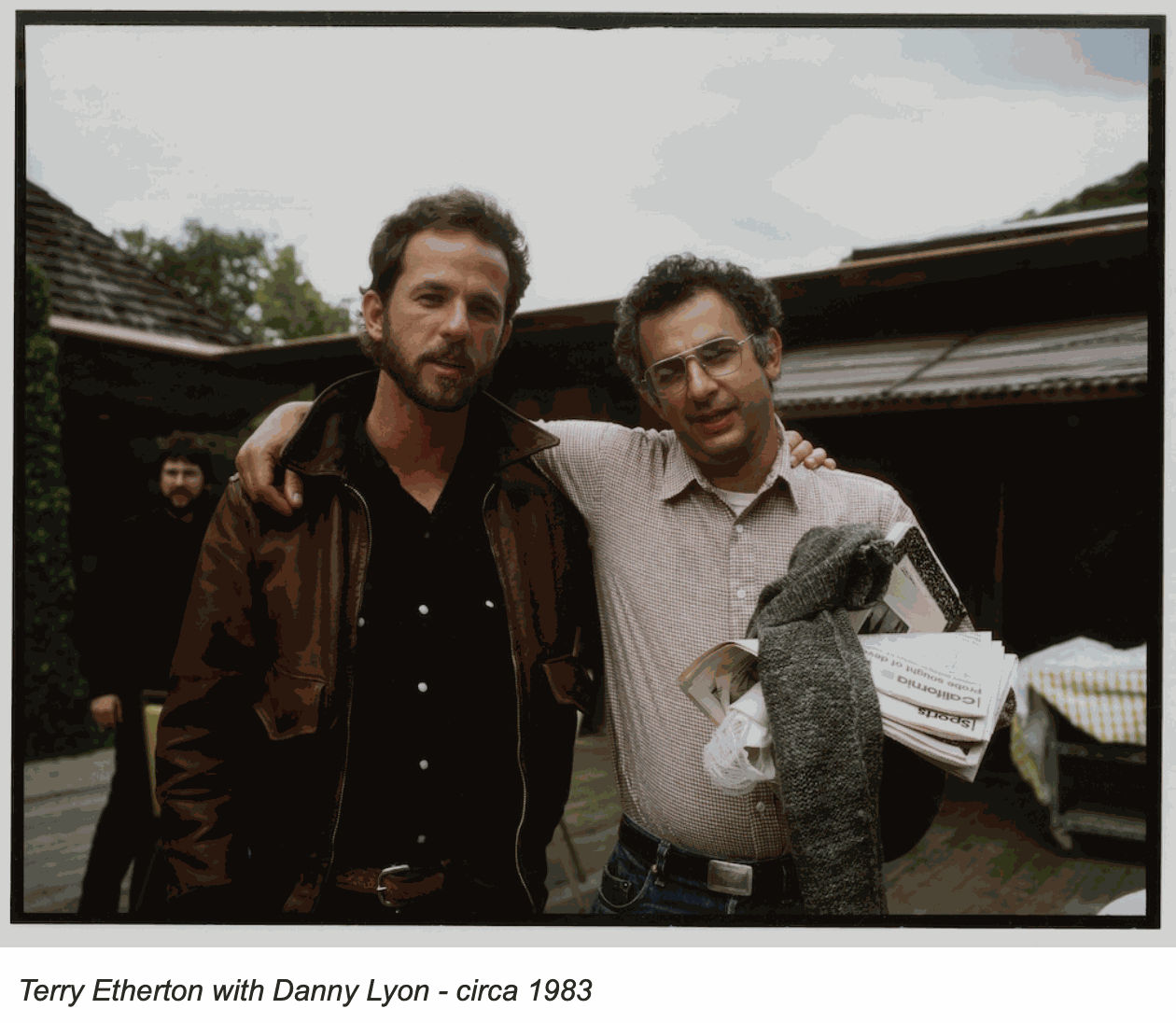

His longest standing professional relationship is with photographer Danny Lyon, one of the most distinguished members of the “New Journalism” movement, whose varied career includes capturing some of the most identifiable photographs of the Civil Rights Movement and the United States’ penitentiary system.

Etherton and Lyon have undergone numerous collaborations, including one that featured Lyon’s photographs of the motorcycle gang the “Chicago Outlaws,” a gang that Lyon had uninhibited access to because he was a member. Lyon’s photo series and his subsequent book is the subject of the much-talked-about Hollywood film “The Bikeriders,” starring Austin Butler, Jodie Comer and Tom Hardy, scheduled for release this month.

“I’m thrilled about this. I know all the characters, and I’ve sold pictures of them. I’ve heard all the audio tapes,” Etherton said. “We are getting so much interest, and questions from the public, as the release of the movie approaches.”

These early trips laid the foundation for his business, because no one else was (no pun intended) going the extra mile like Etherton. The moments he was met with success are some of the memorable of his career.

“On my very first trip – in ’82 – I was in New York and I wanted to show some work to the Museum of Modern Art. The way the rules were, you drop things off on a Tuesday and you pick them up on a Thursday. So, I left several boxes of prints there and I came back on a Thursday and when I did, the assistant said, ‘Do you have a few minutes? Mr. John Szarkowski would like to speak with you.’ I remember thinking, ‘What?’ Everyone knew who Szarkowski is – he’s the curator of photographs at MoMA, and probably the best writer about photography who has ever lived. I kind of idolized him. I had read his books. I remember thinking, ‘how is this possible?’” Etherton said. “That day, he bought eight prints from me. That high stayed with me all the way home.”

Home, or Tucson, has also played a pivotal role in why Etherton has been so efficacious.

In 1975, the Center for Creative Photography opened its doors in Tucson after a meeting with the then-University of Arizona president and Ansel Adams. Adams and four other renowned contemporary photographers – Wynn Bullock, Harry Callahan, Aaron Siskind and Frederick Sommer – wished to permanently archive their photographs there. Today, the number of archival collections has swelled to 270, all of which are open for viewing to the public upon appointment.

“I’m in Tucson for a reason,” Etherton said. “Beyond the fact that I really like Tucson, the Center for Creative Photography is here. If you look across the U.S., every city that has a good photography gallery – like this one – has an institution that collects photography.”

Over the years, Etherton Gallery has gained recognition, aided by its membership in the Association of International Photography Art Dealers (AIPAD), an organization that acts as “the collective voice for the dealers in fine art photography,” and more recently, its affiliation with art dealer websites like Artsy and ArtNet.

Etherton has traveled the world over – Paris, New York, Los Angeles, and elsewhere – attending shows put on by AIPAD. His presence has led to some of his largest museum commissions to-date and allowed him to rub elbows with the world’s wealthiest art collectors (think Graham Nash of Crosby, Stills & Nash, Brad Pitt, and Sharon Stone, among others).

Along the way, he’s developed deep-seated relationships with some of the foremost photographers of our time, including photographer Graciela Iturbide, who has received acclaim for documenting indigenous Mexican cultures, and Joel-Peter Witkin, whose often macabre work is among the most recognizable of the 21st Century.

Yet, despite his incredible success, Etherton never glorifies his accomplishments or himself. He says he’s “just a guy from the Midwest” (he grew up in Carbondale, Illinois), whose greatest talent is simply bringing the right people together at the right time.

“The show that is up right now is by Alanna Airitam and it’s called Black Diamonds. She’s an African American woman who captured African American motorcycle clubs, not gangs, but clubs … I love this show because it kind of dispels the notion of who these guys are. When we had the opening, about a dozen of the people from these pictures showed up on their Harleys with their black and red and white vests.” Etherton said. “At first, these guys had a little trepidation, they weren’t sure what they were getting into. By the end of the evening, they were posing for pictures with their families. It was just awesome … I would say that in my 43 years, that’s one of my top three best openings we’ve had. You had this group of individuals who doesn’t usually interact in a gallery space and our group of regulars, and it couldn’t have gone any better.”

These days, Etherton describes his career as entering a new phase. Though he’s healthy, he’s becoming increasingly aware of his mortality. At 73, he believes he has several years left at the helm, but he also acknowledges he can’t maintain the same clip forever. What that means for Etherton Gallery has yet to be seen, but he suspects in the near-term he’ll begin to scale back on attending AIPAD’s shows and create a succession plan. Most recently, he’s also reacquainted himself with the production work that was emblematic of earlier in his career.

“For years, whenever I go to museums – like for instance if I’m at the Louvre or something – I always like to go and take pictures of the baby Jesus up close. I’m starting to produce these grids – I have one on the wall that’s 49 baby Jesuses,” Etherton said. “For me, it’s not about making photographs so that people can see them. I know I’m not even in the same league as a photographer like Danny Lyon. For me, it’s about the process – I just love doing it. I’m reminded that if all else fails, I know I have that.”