A few years ago Jack Balas put a new spin on all this when he wrote a satirical letter to Art Forum after he counted the number of images of naked women in one issue versus the number of naked men and found a huge disparity. He mockingly recommended that Art Forum do a “boobs to balls” count as gay men and straight women deserved the same measure of titillation the magazine was giving to hetero guys. Of course, he was also pointing to the power imbalance in the selection of whose sexuality winds up on museum walls and why heterosexual male sexual desire is often passed off as art with everyone encouraged to ogle it approvingly.

Another critical point Balas wants to make is that visual depictions of naked males are still shockingly taboo. The American male must, apparently, be depicted in his power suit, dignified, not naked to the world. He cannot be an object of desire – he is the one who gets his desires filled. If you paint a buff, naked guy, this is “beefcake” and you will be labeled and dismissed as a “homoerotic” artist. Nobody, however, ever called anyone a “heteroerotic” artist but the number of those guys has been legion. Even these days the idea of presenting full frontal male nudity does not seem fully acceptable, and the idea of gay men painting gay men for pleasure does not readily find a place in the art gallery world. This situation still reflects a deep-seated and pervasive homophobia, even in the art world, despite all the recent legal gains for the gay community.

Balas definitely paints buff, naked guys, but not necessarily for the sake of painting buff, naked guys. Even when the sexuality of a painting seems raw and in your face, it looks as if Balas might be aiming for something else. In his painting First Draft #1707, Balas toys with our desire for visual titillation. Why is the football coyly covering the guy’s genitals? What’s going on with the arrow connecting the guy with the window? Well, Balas enjoys using text to add dimensions to the visual elements of his work and, reading his text, we read a story of how someone used to ride his bike past this guy’s window when he was younger. The guy would often be in the window, naked, but with the football hiding his genitals. As the days went by, he apparently became more comfortable and he began flipping the football up in the air and catching it.

The image is a first attempt (a first draft) to convey a wry, ribald story, but results in irresolvable ambiguity. Balas points to the fact that we come to galleries, often, to impute our own stories onto visual images and often walk away with nothing. The text resolves any ambiguity and reveals a tale of risky, surreptitious, non-verbal communication and connection. Indeed, Balas creates a type of allegory for art here as finding a way to make the ambiguous understood and universal is certainly one goal. Also, to a great extent, Balas, as a gay male artist who does not shy away from gay male themes, is flipping a football up in the air every time he has a gallery show, forced to wonder whether people are going to be cool with his art or run away in total indignation. Most of us have probably not engaged in this type of exhibitionism, but figuratively we all know what it is like to be conflicted about this type of football flipping moment. Many of us have gotten to the naked with the football moment, but never flipped it. Unlike other folks who use text in art, Balas’s text is often personal and witty, but he strives to make common or universal connections among a general audience. Whether gay or straight, we all have refrained from or taken opportunities to flip the football.

There is, in fact, a huge amount that is both brilliant and enigmatic in the work of Balas, who often will juxtapose differing types of images compelling us to race through interpretations finding connections between the seemingly disparate – Balas seems to be interested in nudging viewers not only toward interpreting but also assessing the interpretive process and our capacities for meaningful or transformative interpretations and what it takes for an artist to really reach another person. Balas also seems to use visual and verbal punning at times and this is most plainly seen in Checkered Passed (Tied) (#1574). Balas writes that the painting “…touches on race and all of the discussions and controversy in the United States these days. The black model has a white arm and the white model has a black arm. Visually thus, they are tied to one another (my original title for the painting was 'Tied'). Further, note the lines literally tying the two models together. However, there is certainly a lot of wordplay going on. Being in a race is one thing, and tying instead of winning is another. The checkered flag signifies the winner in a race. Here the winning flag has been passed to the black model, which is literally pictured in the image. And, the whole history of race in this country is a sordid (i.e. checkered) past.

In my mind the words and the image keep going around in circles—in a great way, and in an optimistic way as well. (It's about time.)"

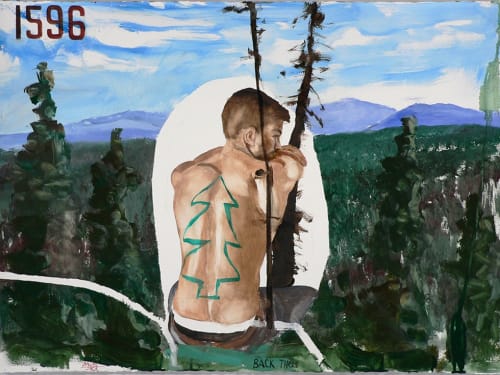

In many reviews of his work it is pointed out that his buff models are in the prime of youth, during a period of life before major responsibilities or concerns, insouciant, unselfconscious, often engaged in athletics or leisure activities or relaxing after some type of physical workout. It suddenly dawned on me that these can, perhaps, be thought of as gay men in the Garden. Not “the garden”, but “the Garden”, Eden. I like to think of these guys as gay men before the Fall. Depictions of Adam and Eve in the Garden are a straight male’s bizarre concept of what the myth of paradise and innocence was like. You get two differing sexes, but in an asexual relationship, cavorting in a hunter-gatherer’s utopia. The woman’s eyes are opened to a knowledge of good and evil, and then the sexcapades begin.

The Western model of spiritual perfection and a fall from perfection is a heterosexual concept often using heterosexual symbolism. In allegorical literature the male represents spiritual desire, while the passive, patient female represents fulfilment of his desire. A gay male has just as much right to wonder what Adam and Steve might have looked and acted like and how they might have handled that tricky snake situation. These are virile, rippling young men who do not derive a sense of shame from being naked. It could be that you can be gay in the Garden, or Balas may be reading Hegel these days and predicting that there will be a future social bliss for all of us.

When Norman Lewis began doing abstraction, and became grouped with the Abstract Expressionists, he was criticized for politicizing art that purported to be universal by including references to the African American experience in his pieces. Ironically, by focusing on his identity, his time and the social circumstances of his people, many feel that his art is more accessible and impactful these days than the work of most Abstract Expressionists. I think Balas might also be in a similar situation. Piquant, insightful, humorous, complex and thoughtful, he may be thought of as a gay artist, when, in fact, he is an artist referring to his identity, his times, his aspirations for himself and his companions. I feel that when all is said and done, Balas will be recognized for his significance and considered a trail-blazer on many levels.